As veterinary professionals we are all aware of the importance of safety in the workplace. If you do not have it already, an OSHA safety program specific for your hospital is highly recommended (www.aahanet.org/Store/StaffTraining.aspx ) for the Be Safe series of DVDs from AAHA). www.vetmedteam.org has ongoing courses called “Demystifying OSHA” for both management and staff.

Aside from OSHA regulations, there are a lot of common sense safety precautions that all staff should be aware of. We all know of the common dangers in the hospital – injuries from animals being the top fear of them all (or at least it should be!). Future topics will deal with zoonotic diseases, radiation and anesthetic safety, etc.

Fractious pets are always a challenge. Many of those who are new to the profession take more chances with their safety than is wise. Not only do you put yourself at risk, but also any staff member who is assisting you, as well as the pet. Just “grabbing” an angry cat, for example, is not brave and admirable but rather shows inexperience. There are numerous techniques to ensure employee safety and reduce anxiety and stress for the pet (and your employer should appreciate fewer workmen’s comp claims). Remember, an elderly or debilitated animal can die from stress. Remembering to “first do no harm” goes a long way in these situations.

I know there are numerous methods for taking time with pets and reducing their anxiety so some of the following techniques do not need to be used. In fact, there is an article in the June 2011 issue of Veterinary Technician called “Inside Behavior – 10 quick ways to improve patient handling” by Alicea Schaeffer, and can be accessed via www.vetfolio.com. The methods she discusses are definitely good options for your hospital to consider using as set protocol. However, the purpose of my article is to help you when you find yourself in a difficult situation with a pet and you need to complete a procedure safely for all and in a timely manner.

Some techniques you can try include the following:

- Completely wrapping a cat in a towel (a “burrito”) with only the part of interest exposed (for example a leg for venipuncture), often using a muzzle as well. This method can also be used for mask sedation. Incorporate the towel into your “scruffing” hand to keep it snug enough around the cat’s neck so he can’t push his front legs through.

- Chemical restraint. For fractious/feral cats this usually means an inhalation chamber. If you are not so fortunate as to have a genuine inhalation chamber, a Wal-Mart/Target storage bin with a hole cut in the top to allow flow of anesthetic gas can be used. Not the best situation but it works if that is all you have. Remember when using this that the cat needs to be monitored very closely and removed from the box the moment it is sedated. Throw the box outside so you are not breathing the gas. Put the cat on a mask, monitor and complete the procedure.

- This box also comes in handy if you have a loose fractious cat – if you are good (and agile!) you can put the box over the cat and trap it, then slide the lid underneath, latch it, turn it over, and there you have him. Safe with no one getting hurt.

- Check out this video on a product called “clipnosis calming clips”. I would love to know what you think!

- If a dog can be safely muzzled and there is an experienced restrainer, that is often all that is needed. The saphenous vein on the hind leg can also be used for venipuncture. Dogs may tolerate this better than a frontal approach using the cephalic or jugular vein.

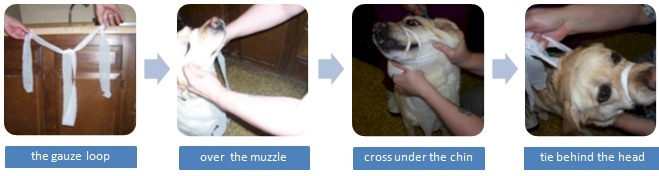

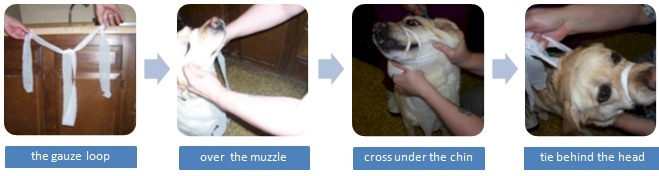

- Remember you have to get fairly close to a dog’s biting end to muzzle him! If this cannot be done safely, you can try using a long piece of roll gauze tied in the middle with a half square knot, producing a loop. Try to swing this over the muzzle and then pull tight, cross both ends underneath the muzzle and then tie behind the head (of course someone needs to be behind the dog to keep him from backing up out of the muzzle during this procedure). The long gauze gives a better safety margin; only use good quality gauze as the “cheap stuff” can break at the worst time! Once the gauze muzzle is in place, if needed a regular muzzle can be applied over top for more security.

- If a dog cannot be safely muzzled, the leash can be put through a cage or run door and the dog’s head restrained just long enough for an IM injection of a sedative, such as domitor, to be given.

There is another product for cats that I used many years ago, called the “wild child”. It is an ingenious squeeze box with a lid that lowers down and locks at one of 3 different levels. The box and lid have several holes that can be used for injections once the cat is immobilized. It is safe for all and allows procedures to be completed quickly. See www.veterinaryconcepts.com

These are just a few suggestions I have found to work, and I hope it will encourage you to think about some of your favorite techniques. We would love to hear some of your ideas; make this your forum. Good suggestions will be included in future issues of “Don’t Get Hurt…”.